Two New Zealand artists, Daniel Reeve and Michael Barker, explore myths and legends from around the world, ancient to contemporary, in this exhibition in Toi Gallery at Pataka Art + Museum in Porirua. Daniel and Michael use traditional techniques of brush, pencil and pen to interpret a range of myths (narratives with elements of fantasy and the supernatural) and legends (historically-based folktales, enriched and embellished over time).

Click on a thumbnail below to see a larger image, or simply scroll down the page to see all the paintings and the stories that accompany them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE FLYING DUTCHMAN

Daniel Reeve

Acrylic on canvas

THE STORY: Sightings of the ominous ghost-ship the Flying Dutchman have been reported since the 18th century, by superstitious sailors,

who believe it to be a portent of ill fortune.

Legend has it that the Flying Dutchman - De Vliegende Hollander in Dutch - came to grief while trying to round the Cape of Good Hope in a fierce tempest.

The ship foundered, with all lives lost. Ever since then, in very bad weather, the ship reappears, still trying to round the Cape.

Some say the Master of the vessel refused to shelter in Table Bay, swearing "May I be eternally damned if I do, though I should beat about here until

the day of judgement" - and he must now abide by that curse, doomed to sail the oceans forever, never allowed to make land. Sinister overtones

have been added to the tale over the years, with the ship's eternal predicament being punishment for some horrendous crime on board, or the crew being

stricken with a pestilence.

In any case, sailors over the years developed a wild superstition concerning sightings of the phantom ship, always in foul weather,

and always foreboding bad luck.

The story of the Flying Dutchman has been re-told many times, in literature, opera, theatre, film and TV; and the name is sprinkled through many other walks of life.

As well as the ship, this painting features the map of the area of the story's origin: the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa,

with the placenames as they were in the 1800s.

THE MIRROR

Michael Barker

Oil on canvas

THE STORY: The painting evokes The Lady of Shalott painted by John William Waterhouse (1898), which represents the climatic ending of the poem (1832)

of the same name by Alfred, Lord Tennyson. In the poem, the poet describes the tragic plight of a young woman, loosely based on the Arthurian figure of

Elaine of Astolat, who yearns with unrequited love for the knight Sir Lancelot. Isolated under an unknown curse in a tower near Arthur's Camelot, she is

destined to only view the world through a mirror. Defying the curse however, she looks directly out the window at Camelot and her fate is sealed and she

dies in a boat within sight of that legendary place.

The painting depicts a likeness of the boat from Waterson's painting on the mirror-like lake in the beautiful gardens at Fernside, near Featherston, in

the Wairarapa region of New Zealand's lower North Island, famed as being the location for 'Lothlorien' in Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

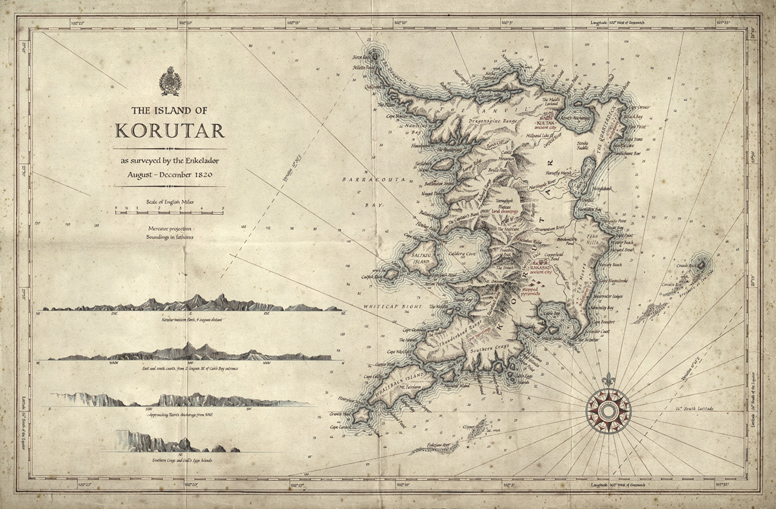

KORUTAR

Daniel Reeve

Ink and watercolour

THE STORY: The obscure legend of the island of Korutar was re-awakened in the late 1800s when a folder containing a map and drawings

from the ship Enkalador was discovered in Concepción, Chile, where it remains to this day.

The island itself differs in some respects from the earlier, imaginatively drawn Loska Chart, upon which the prior legends seem to have been based.

But essentially, these new documents lend weight to the original stories, with their accounts of the remains of the civilization that once dwelt

on the island, with their cave paintings, sculptures, pyramidal structures, indecipherable hieroglyphs and huge land drawings. Apparently, the vast

drawings could be seen clearly from the island's highest peak. Remnants of previous drawings could also be discerned from this viewpoint - the drawings

may have been changed seasonally, or annually, or perhaps over a longer time period. A link between these and the Nazca Lines of Peru seems probable,

as does a link between Korutar and its nearest neighbour, Easter Island.

But all remains conjecture. Despite being carefully charted in the early 1800s, later expeditions that century failed to find the island,

and it was assumed that tectonic/seismic events had sent it to a watery grave.

This piece attempts to re-create the Enkalador map from the images available; an exercise in cartography from the age of exploration.

THE SEA KING

Michael Barker

Pencil on Hahnemühle paper

THE STORY: Among the traditions of Rarotonga (Cook Islands) comes the story of Tu-tarangi (c. 450 AD) famed navigator and coloniser of Avaiki-raro,

extensive widespread islands of eastern Polynesia including Fiji, Tonga and Samoa. Tu-tarangi may be considered archetype of the great Polynesian

navigators, truly 'sea kings', who followed, such as the legendary Kupe and others, whose great navigational skills, based on such traditional methods

as the 'star-compass', saw them travel vast distances of the Pacific Ocean and settle all corners of the Polynesian triangle from Hawaii, Rapanui

(Easter Island) to Aotearoa (New Zealand).

This drawing celebrates this navigational tradition and the superb ocean-going vessels these ancient mariners used. In the story depicted Tu-tarangi

also possessed two prized fishing birds Aro-auta and Aro-a-tai which illustrate the close connection between the navigators and the natural world to

which they belonged. In Aotearoa the two birds are celebrated in two mountain peaks of the same name in Te Aroha in New Zealand's upper North Island,

the artist's ancestral home.

TANIWHA

Daniel Reeve

Acrylic on canvas

THE STORY: Taniwha are the mythical guardians - kaitiaki - of all waterways and seas of Aotearoa, and are held in awe, fear and great respect.

They lurk in deep pools and in dangerous places, where there are unknown depths or deceptive currents or big waves. Taniwha feature in many Maori myths.

Some take on protective roles over the people of the tribes with which they're associated.

As a little boy, I was always afraid of this creature, thanks to my father's warning 'Watch out for the taniwha!' whenever we played in or near the water,

especially the creek at the back of the house. Any log floating in a river might have been a glimpse of the taniwha. It might be hiding in the kelp at the

beach, or in the surf, or lurking below me as I swam and sailed in the sea.

My painting is an attempt to capture something of the essence of the taniwha. Lurking, hard to perceive clearly. Is that seaweed, or is it arms and fingers?

Whenever you're in or on or near the water, watch for the Taniwha....

NGAKE AND WHATAIAI

Daniel Reeve

Watercolour

THE STORY: Ngake and Whataitai were taniwha brothers who lived in a lake at the tip of Te Ika a Maui (the North Island). Whataitai was gentle-natured

and peaceful, content with swimming slowly around the lake. But Ngake was very active, fit and strong, and filled with curiosity. He could hear the cries

of the seabirds and the noise of the ocean near the southern edge of the lake. The birds told the brothers about the vast, never-ending ocean, filled with

wonderful things and many kinds of fish.

Ngake became dissatisfied with being trapped in the lake, and longed to escape and explore the ocean. One day he could stand it no longer. He swam to the

north end of the lake, whipped his tail so violently that it created the Hutt River, and hurtled toward the southern shore of the lake. With a huge burst

of energy, he leapt to escape. He crashed into the thin stretch of land between the lake and the ocean, creating a channel. With a bit more thrashing,

he broke through the remaining rocks, and he was in the ocean at last! He swam off to explore its depths.

With its southern wall broken, what was once a lake is now Wellington harbour, with Ngake's channel connecting it to the ocean where he escaped.

Whataitai missed his brother, and decided to follow him. He copied what he had seen Ngake do, but he wasn't as fit and strong as Ngake, and a lot of water

had flowed out of the lake into the sea, so the water was shallower than before. He leapt as well as he could, but he didn't make it: he landed on the strip

of land, and was stuck. He didn't have the strength to thrash his way to the sea.

Eventually an earthquake raised him high and dry, and he died, and his body became the rocks and earth, the hill that is now called Hataitai.

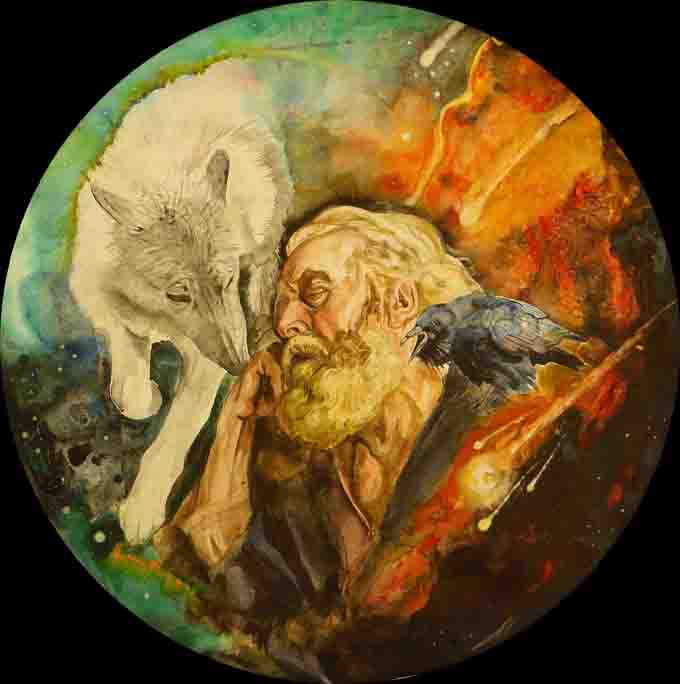

VISIONS IN AN ANCIENT VALE

Michael Barker

Watercolour on Hahnemühle paper

THE STORY: The painting celebrates the highly complex and mysterious concept of 'shamanism'. The word 'shaman' has its origins in the Siberian word

'saman' and is derived from the word scha, to 'know'. So shamanism refers to someone who knows, who is wise, a sage. Among indigenous tribes,

most notably those of Asia and the Americas, though not exclusively, a shaman played the role of healer deliberately altering his or her consciousness

in order to obtain knowledge or power from the world of the spirits in order to help, cure and protect members of the tribe.

In this painting the shaman represented by a figure by J M Vien connects with two formidable and familiar spirit animals, the wolf and the raven,

messengers which come to him in a vision and dream. Traditionally powerful symbols, the wolf was seen as 'powerful protector' and the raven as 'keeper of secrets'.

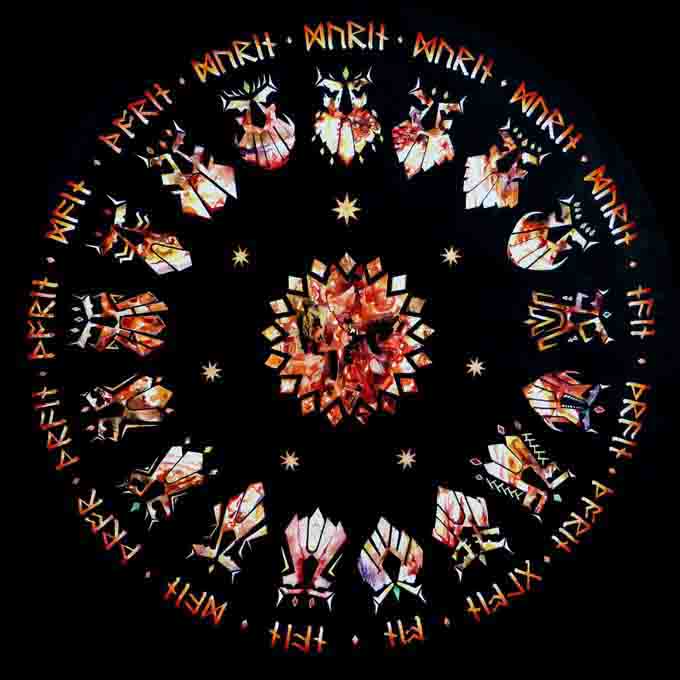

THE GREEN ROSE

Michael Barker

Watercolour on Hahnemühle paper

THE STORY: The painting is an interpretation of the 'Green Man,' a mythological being primarily interpreted as a symbol of rebirth, representing the

cycle of new growth that occurs every spring. Most commonly depicted in sculpture, or other representations his face is surrounded by leaves, branches

and vines. The 'Green Man' is found in many cultures and in many ages around the world and is often related to natural vegetation deities. In Britain it

has been linked to the Celtic-Romano deity 'Viridios' which derives its origins from the Latin word viridis meaning 'fresh, green or vigorous'.

The painting, in 'ecclesiastical rose' format, also features in one stylised depiction two noteable personalities of British botany, David Bellamy and

Monty Don as well as plants and trees sacred to the ancient Celts.

NARCISSUS AND ECHO

Daniel Reeve

Acrylic on canvas

THE STORY: Fearing that trouble would be caused by her son's striking beauty, Liriope entreats Tiresias to read his future. "Fear not," says the oracle.

"So long as he fails to recognize himself, Narcissus will have a long and happy life."

True - but it isn't long before fate overtakes him. Separated from his hunting party one day, Narcissus rests beside a pool....

Enter the once-talkative mountain nymph Echo, whom the Queen of the Gods has recently cursed never to speak again, except to repeat the last few words

spoken to her. She instantly falls in love with Narcissus - but her curse causes their meeting to go awry, and, rejected by Narcissus, she flees, heartbroken.

Aphrodite answers Echo's plea to be released from her misery, by freeing her from her bodily self, leaving only her voice, doomed to forever repeat the last

few words she hears. You can still hear her voice today, in places where sound reverberates.

Meanwhile Narcissus returns to the object of his fascination: the beautiful face he can see in the pool. He cannot tear himself away; he is spellbound.

He has fallen in love with his own reflection, and he stays beside that pool, day after day, gazing longingly at himself until at last the Gods take pity

and turn him into a beautiful yellow flower.

That flower is of course the daffodil - scientific name Narcissus - which to this day bends its head to admire itself in pools and puddles.

The story comes from ancient Greek myth.

WILD THINGS

Michael Barker

Watercolour on Hahnemühle paper

THE STORY: The painting is a study of 'nature spirits' and faerie. Historically, the term 'faerie' was used adjectively to mean 'enchanted' but

also generically to describe 'enchanted' creatures, generally human in appearance and having magical powers. Influences from a variety of cultures and

epochs have combined to give us multitudinous range of creatures with diverse personalities from benevolent to malevolent and in between.

In this painting nature spirits are depicted as guardians of nature, or 'kaitiaki' (Maori: 'guardians'), shy and slightly sinister such as those found

in Maori folklore, particularly 'patupaiarehe' (trnsl. 'fairy folk') and also the naiads of Greek mythology. It is inspired by familiar wild places

frequented by the artist, particularly riverbanks, of New Zealand's King Country of the central North Island.

THE BLOOD ROSE

Michael Barker

Watercolour on Hahnemühle paper

THE STORY: The painting explores the origins of the mythological world of JRR Tolkien's Middle-earth, in particular the realm of the 'Dwarves.'

It seeks to illustrate in watercolour the genealogical line of 'Durin,' whose origins were found in Norse mythology, in particular the poem 'Völuspá'

from the Poetic Edda.

According to Tolkien, 'Durin the Deathless' awoke at Mount Gundabad in the north of the Misty Mountains, and within the mountains created the great

city of Khazad-dûm, known by the Elves as Moria. He founded a line of dwarves known as the Longbeards or Durin's folk, which was ruled over by kings.

While no complete list of all the kings was known, it was believed that at least four of the kings after Durin were reincarnations of himself.

CURTANA

Michael Barker

Pencil on Hahnemühle paper

THE STORY: In the world of popular culture, particularly movies, characterised as it often is by vengence, it is refreshing to recount a story of mercy.

Such is the story of the sword 'Curtana', which exists in both legend and reality. It currently resides as a Crown Jewel and is used in inaugural

ceremonies of the British Crown and is the subject of many stories.

According to one legend, Ogier the Dane was bequeathed a sword of that name reputedly "of the same steel and temper as Joyeuse and Durendal"

(Bulfinch's Mythology). Ogier's son was killed by the ill-tempered Charlot, son of the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne who refused to punish his son.

In an act of vengence Ogier sought to slay Charlot, but an angel appeared and knocked the sword from his hand, breaking the blade, and exclaiming

"Mercy is better than revenge!"

From then on Curtana was known as the 'Sword of Mercy'.

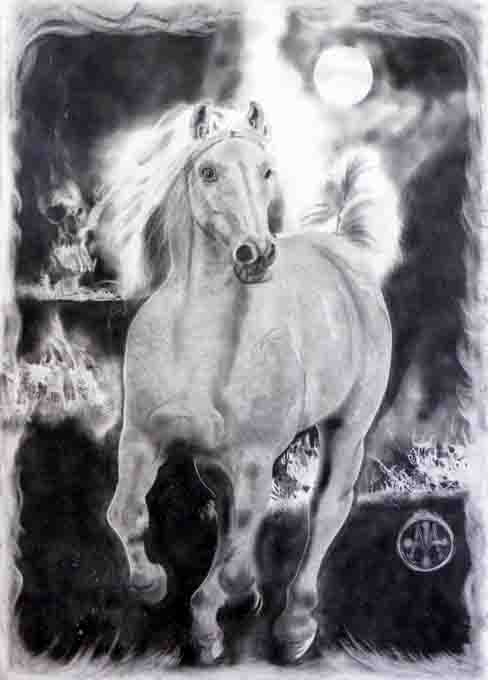

THE PALE HORSE

Michael Barker

Pencil on Hahnemühle paper

THE STORY: The 'Pale Horse' is a figure in Christian faith appearing in the final book of the New Testament, the 'Book of the Apocalyse', also known

as the 'Book of Revelation'. Its colour is significant being the colour of death or sickness as in the pallor of a corpse. While most commentators

correctly associate the apocryphal writings of the New Testament with first century Rome and the associated persecutions of Christians of that time,

in our own times there is no doubt that we are also witness to death, pestilence and disease as well as natural disasters on an apocryphal scale.

The drawing was inspired by images of terrified horse escaping wildfires in California, a metaphor perhaps of the world as it has become often

unpredictable, sick, terrifying and broken.

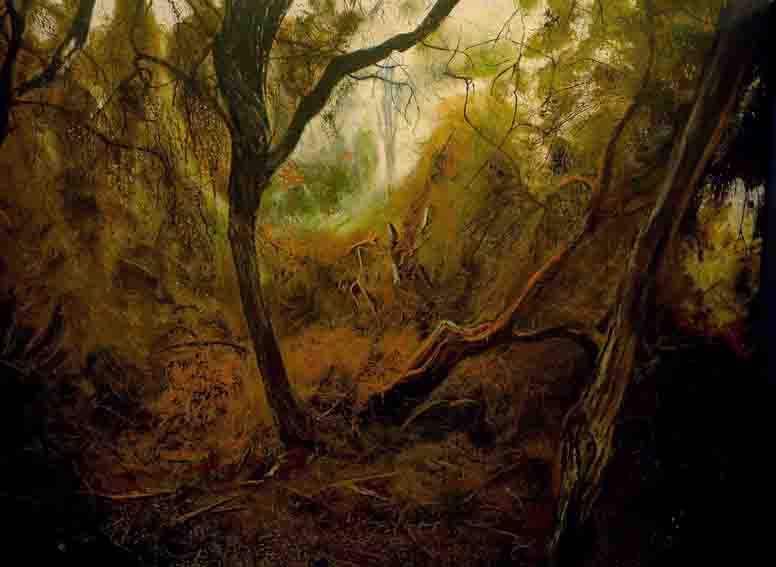

THE GOLDEN BOUGH

Michael Barker

Oil on canvas

THE STORY: The painting evokes a scene from the ancient Roman epic Aeneid by Virgil in which the Trojan hero Aeneas wants to enter the

underworld to consult with his dead father. The 'Sybil of Cumae' tells him that he needs to offer a golden bough from a sacred tree to Proserpina,

queen of Pluto, king of the Underworld in order to enter. The story has inspired a number of artists including J M W Turner who created a painting

The Golden Bough in 1823. Turner's painting in turn was evoked in the influential book of the same name, by James George Frazer in 1890 in

which Frazer speculatively constucts a thesis connecting myths with religious practices.

This painting was inspired by the sulphur-enriched and otherworldly scenery of the Wai-o-Tapu thermal park south of Rotorua in the central

North Island region of New Zealand.

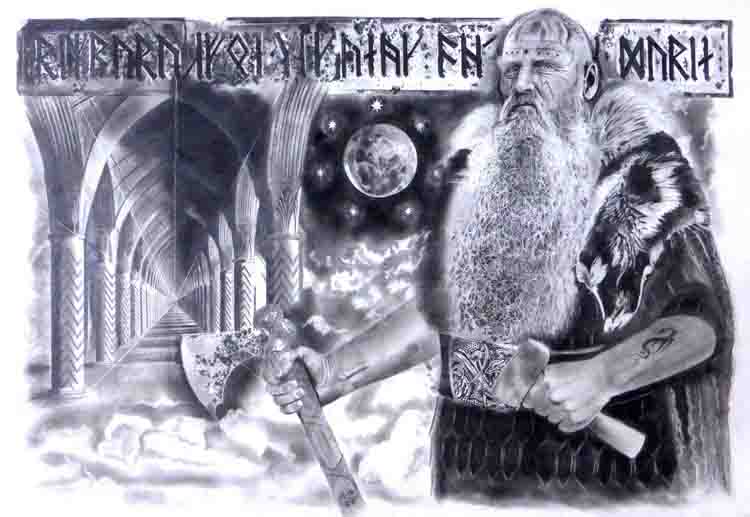

THE MOUNTAIN KING

Michael Barker

Pencil on Hahnemühle paper

THE STORY: The drawing is a study of the Tolkien character 'Durin I', also known as 'Durin the Deathless' due to his longevity, first of the seven Fathers of the Dwarves, first king of the 'Longbeards' and the founder of the city of Khazad-dûm. Having 'awoken' in Mount Gundabad in the northern Misty Mountains, Durin wandered until he founded the city of Khazad-dûm in the natural caves beneath three great peaks of the Misty Mountains: Redhorn, Silvertine and Cloudyhead. The city, populated by Longbeards or Durin's Folk, grew and prospered continuously through Durin's life, its power enriched with the discovery of 'mithril,' a magical, extremely valuable and nearly indestructible metal found only in its mines. A descendant of Durin, in a long line of kings, was the legendary Thorin Oakenshield, a central figure in The Hobbit. As inspiration for Durin, Tolkien drew on the Völuspá, first poem of the Poetic Edda, the collection of old Norse poetry, from which all the names of all the noteable dwarves of his epic stories The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit were drawn. The runes illustrated in the drawing depict a suggested motto for Durin... 'We were never conquered!'

MIDDLE-EARTH

Daniel Reeve

Ink and watercolour

THE STORY: Tolkien created an extensive mythology - far more extensive than many people realize. It forms the foundation upon which his famous

books The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are built - and the arena of action for those books is, of course, Middle-earth.

Daniel worked on Peter Jackson's trilogy of films, The Lord of the Rings, doing calligraphy and creating maps. In an extension to that work, Daniel

created this map for the film company, re-drawing Tolkien's map of Middle-earth, creating a new cartouche and borders, and colouring

it with watercolour - all on a $7 sheet of printmaking paper in his garage in Titahi Bay. When the films were released, the map became a global icon,

forming a central part of all the film's merchandising and publicity.

THE MISTY MOUNTAINS

Michael Barker

Oil on canvas

THE STORY: Of the great geographical features of JRR Tolkien's Middle-earth, one of the most significant are the Misty Mountains,

a chain running 900 miles, and lying between the region of Eriador in the west and the great River Anduin in the east. Dominating the mountains

are five great peaks, Mount Gundabad in the north, Redhorn, Silvertine, Cloudyhead in the centre and Methedras (The Last Peak) in the south.

The lands in the shadow of the mountains included forests, rivers and the realms of Angmar, Dunland, Lothlorien, Fangorn and others. The Great Dwarven

city of Khazad-dûm (later called Moria) was located near the middle of the chain near the Redhorn Pass.

Tolkien's Misty Mountains find their inspirational roots in the legend of Skirmir found in the Poetic Edda, the collection of anonymous Old Norse poems.

In that story, the hero Skirmir has to pass over them but with ever present threat of mountain giants and troll caves.

This painting is inspired by the 'Pinnacles', five peaks of the Whakapapa region of the central North Island of New Zealand.

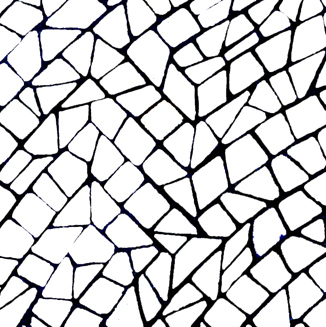

LABYRINTH

Daniel Reeve

Acrylic on canvas

THE STORY: From the Ancient Greeks, and the myth-rich island of Crete, comes the story of the Minotaur, who lived in a maze - the Labyrinth - created

by the famed inventor and architect Daedalus, for King Minos.

The half-bull, half-man Minotaur, unnatural offspring of Minos' wife Pasiphaë and the snow-white bull which Minos had refused to sacrifice to Poseidon,

lived out his life in the centre of the Labyrinth, sustained by devouring humans sent into the maze by Minos.

Eventually the hero Theseus volunteered to kill the beast. Aided by Minos' daughter Ariadne, who supplied him with a ball of thread to allow him to

retrace his steps through the Labyrinth, Theseus killed the Minotaur, releasing him from his sad, miserable life.

In keeping with the tragic elements of Greek myth, Theseus' father Aegus suicidally leapt into the sea (thereafter named after him: the Aegean Sea),

when he saw black sails on Theseus' returning ship, instead of the white sails that were to indicate victory over the Minotaur.

Painting the LABYRINTH

Paint the Labyrinth. Do it as a mosaic, in Mediterranean blues, to add to the Cretan aesthetic. That was the idea that came into my head one day.

Pretty simple so far. But then came a few challenges....

Designing a labyrinth that works, while maintaining a kind of visual symmetry and elegance, is quite a tricky problem - but I think I've come up with

a satisfactory maze. Then the possibilty of adding the Minotaur's head occurred to me, so I had to design that, too. Next I made a digital mock-up, to

finalise the size and positioning of the head, and to decide whether the walls looked better dark on light, or light on dark.

To see the pattern of the walls, they need to stand out from the background by contrasting from it: either contrasting in tone or contrasting in

colour - or both. And the Minotaur head must also be in contrast from ITS background. Again, by tone or by colour.

The simplest solution would have been to allocate three levels of tone - light, medium and dark - and paint each of the three features - the walls,

the Minotaur and the background - in those tones. That would work, but it would have been difficult (to achieve) and uninteresting (to look at) to

stick to three tonal bands for the three features.

I wanted more variety than that; I wanted the walls and background (and Minotaur) to be made up of a variety of colours and tones, all mingled and

fragmented - so that the three features all overlap, to some degree, in the variety of their colours and tones. Indeed, in some places I've allowed

the walls and background to be distinguished from each other ONLY by colour (for example, purple walls versus green paths), with neither component

being lighter nor darker than the other, by any great degree. And in another part I made the paths LIGHTER than the walls, whereas they are usually

darker, on average.

Also, I wanted to keep the Minotaur quite subtle, keep his outlines ambiguous, sometimes blending with the background, sometimes contrasting from it - so

that you basically see the maze first, and the bull second. For this, the variety of tones became an advantage.

This plan only evolved as I painted the thing. And also as I painted, I introduced another element (and another level of difficulty for myself): making

patterns of shape and colour in the background itself, to add another layer of interest and visual appeal. So now there were also bands of colour and

tone running through the background: seams of blue, patches of purple, oceans of variegated dark blues, etc.

So the painting developed, the final plan only maturing as the piece neared completion. But in the meantime, I had another problem to deal with:

the ambiguity of how the eye interprets the tesserae that make up the walls and paths....

With all the mixing of colours and tones, there came several occurrences where a block that was supposed to be part of a wall appeared to be a track

connecting one pathway to another! And the reverse situation occurred several times too. Tricky!

So on a micro scale, I found myself having to carefully select the shapes, placements and colours of the blocks, in order to indicate conclusively

where the paths led, and where they intersected or forked, and to make sure that no parts of the walls could also act as unintended shortcuts between paths!

It's not perfect or foolproof, of course, but I tried to make it so that even if you drain all the colour and tone out of the blocks, you can STILL see

where the paths and walls are, and not accidentally cross from one to the other.

The meander pattern around the edge was another late addition (after transferring the labyrinth design to the canvas), but it works well to break up

what would otherwise be large empty areas, and again, adds another level of interest, and strengthens the ancient Greek aesthetic.

The gold tesserae were always planned, but it's a happy accident that gives them the appearance of a constellation of stars, in different lights and

viewing angles.

A very intriguing piece to paint; one that involved evolutions of both the plan and the work, until they converged and aligned at the moment of completion,

better than the concept they started from.

Photos from the Opening